“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death”

-Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry

The Voice of Liberty

by Rev. Scott Elliott

In May of 1736, Patrick Henry was born to John Henry, a Scottish immigrant. John Henry was part of the Anglican church and his brother was an Anglican minister named Patrick who he named his son after. His mother, Sarah Winston, came from well to do family and she became part of the presbyterian church during the great awakening. When he was a boy, his mother took him to a series of revivals held by Samuel Davies and had she would have him recite the sermons back to her on their ride home. The influence of preachers like Davies and George Whitfield laid the foundation for Henry’s reputation as a great orator. With his parents going to different churches Patrick found himself being influenced by both denominations.

Eventually when he was old enough, he ran a dry good store for his father. His father was well educated became a judge at the Hanover courthouse. Patrick didn’t receive any formal education, but was taught well by both his father and uncle. At age eighteen he married Sarah Shelton, and not long after, had his first of seventeen children, Martha. For three years he worked as a tobacco farmer during a drought and then his home burned down and he lost everything. They moved into Sarah’s father’s tavern across from his father’s courthouse. Patrick worked as the innkeeper and he listened and learned from the lawyers who often discussed cases in the tavern. Within six months he learned enough to get his law license in Williamsburg. Some early fame came from defending Baptists who were being persecuted in Virginia. Because of the drought, Virginia had less tax revenue coming in from tobacco crops. As a result, the colony decreased the wages of anglican ministers. A minster then sued the colony for backpay. The case was called the Parson’s Cause and Patrick’s dad was the judge. After a lengthy nineteen month trial the judge ruled that the minister was due his wages. The question was how much he needed to be payed. That’s when Patrick was brought in to represent the Virginian government. He attacked the ministers for being greedy and accused the anglican ministers of not caring for people. His argument was so passionate and effective that they awarded the minister the equivalent of only one penny. By 1765 he was elected to the house of Burgesses to represent the voice of the people. He was twenty nine years old.

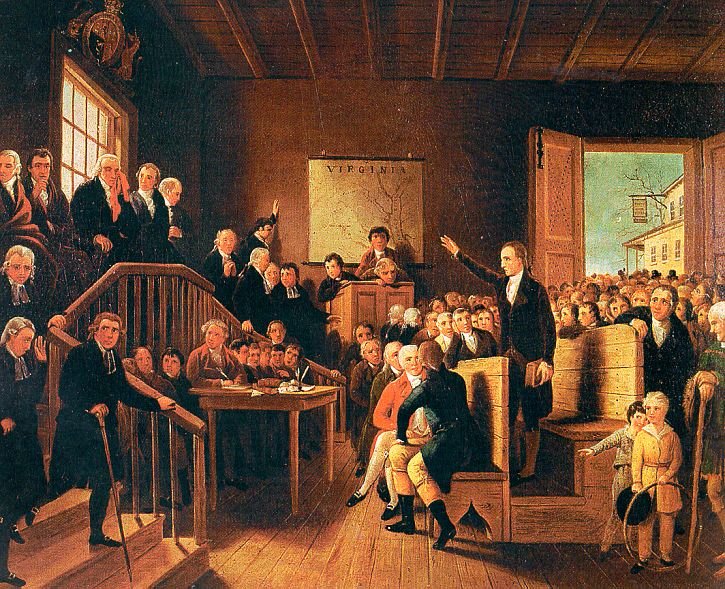

In his first week he listened as the house debated the Stamp Act. After listening and discussing the matter he wrote four resolutions. On the 29th of May he read his resolves which protested the Stamp Act. He argued that only the Colony of Virginia should have the right to lay taxes on its inhabitants. He asked to speak again in the house the next day. What he spoke the next day was a threat to the crown itself. This is depicted in the famous painting that people know so well. Many people shouted that this was treason. While there isn’t a record of his exact words, it was reported that he said, “if this be treason, make the most of it.” His Stamp Act resolves were printed and then widely circulated among the people. This led to the phrase, “no taxation without representation.”

Henry continued practicing law but also took up farming again to help provide for his family. He purchased a plantation called Scotchtown from the father of Dolley Madison. The property he purchased came with slaves. He was not in favor of slavery, but he thought they would be better off under his care than out on their own. He said, “Is it not amazing, in a country above all others fond of liberty, that in such an age and such a country we find men professing a religion the most humane, mild, meek and generous, adopting a principle as repugnant to humanity as it is inconsistent with the Bible and destructive to liberty.” After his wife gave birth to their sixth child she began to struggle with mental illness. Patrick didn’t want her to be put into a mental hospital so he kept her at home where she could receive better care.

In 1774 the House of Burgesses was dissolved by the colonial governor and a continental congress was called in Philadelphia. Seven delegates were sent from Virginia including Patrick Henry and George Washington. In Philadelphia he met Samuel Adams. Both were convinced that war was inevitable. It was here in Philadelphia where Henry first said, "The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more. I am not a Virginian, but an American.” In February of 1775 Patrick’s wife passed away. Not long after a second convention was held, this time at St. John’s church in Richmond, Virginia. This time there were one hundred and twenty delegates in including both Washington and Jefferson. Henry listened for three days with out saying much, but on March 23rd he spoke:

“There is no retreat but in submission and slavery! Our chains are forged! Their clanking may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable—and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come.” When Henry paused, murmurs of “Peace! Peace!” emanated from the pews where some of his timid colleagues sat, punctuating the dramatic moment and prodding one of history’s greatest orators toward the culmination of his most famous speech. “Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace,” Henry answered, echoing the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah, “but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field!” he exclaimed, affirming once again Virginia’s policy of steadfast unanimity with the other colonies. “Why stand we here idle?” Slumping so vividly into the posture of a hopeless slave that onlookers perceived manacles “almost visible” on his wrists, Henry asked, “Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” He paused again, lifted his eyes and hands toward heaven and prayed, “Forbid it, Almighty God!—I know not what course others may take, but as for me . . . give me liberty, or give me death! Then as his voice echoed through the church and his audience watched in stunned silence, Henry raised an ivory letter opener as if it were a dagger and plunged it toward his chest in imitation of the Roman patriot Cato.”

Henry’s speech is perhaps his most well known accomplishment and the words, “Liberty or Death” live on in the minds of Americans today. Five months later he was commissioned as colonel of the 1st Virginia Regiment.

On May 15, 1776 Virginia passed a resolution declaring their independence as a state. On June 12th they passed a Declaration of Rights. On June 29, 1776 Henry was elected the first Governor of the state of Virginia. Henry was sworn in on July 5th, 1776. One day after America declared independence. The next year in 1777 he married his second wife, the cousin of Martha Washington. When Washington was at Valley Forge Henry sent food and supplies to aid him. In 1794 Washington wrote, "I have always respected and esteemed him; nay more, I have conceived myself under obligation to him…” Henry served three terms as Governor, the maximum allowed under the constitution. His replacement was Thomas Jefferson. The two of them had a complicated relationship. They were at one time friends, but Jefferson saw Henry as more of a country man with less education and simpler taste.

In 1784 Henry was elected governor for a second time. One author wrote, “Although a constitutional figurehead, Henry remained the most revered patriot in America after Washington and Virginia’s most powerful leader—indeed, one of America’s most powerful leaders.” In 1787 the Constitutional Convention adjourned and Washington sent a copy of the constitution to Henry. But Henry did not support it because it did not include a Bill of Rights. He also feared that it gave too much power to the federal government.

Ultimately Henry spent his remaining years struggling with some health issues, but devoting his time to his family. One of his grandchildren described him at the end of his life saying, “He spent one hour every day in this office in private devotion. His hour of prayer was the close of the day including sunset. He usually walked and meditated, when the weather permitted, in this shaded avenue. He rose early in the mornings of the spring, summer, and fall, before sunrise, while the air was cool and calm, reflecting clearly and distinctly the sounds of the lowing herds and singing birds.”

In 1794 George Washington offered Patrick Henry a seat on the Supreme Court but he declined it. Washington later offered him positions as Secretary of State, Minister to Spain, and Virginia Governor again. All of these he declined to spend his time focusing on his health and family. When John Adams became president he offered Henry the position of Ambassador to France, but he declined. Finally Washington convinced him to run for the legislature and he was elected unanimously. Shortly after on June 6, 1799 Henry passed away and was buried at his home in Red Hill, Virginia.

His first born daughter Martha married Col. John Fontaine and they named their firstborn Patrick Henry Fontaine who also became a colonel. He in turn named his daughter Martha Henry Fontaine. Martha’s son moved to California during the Gold Rush to the city of Ione where the family lived for four generations. The last of the family there was my grandmother Marian who named her firstborn son Patrick, my uncle.

Thomas Jefferson said Patrick Henry “was our leader in the measures of the Revolution in Virginia… In that respect more is due to him than to any other person. . . . He left us all far behind.” Henry’s legacy lives on as the voice of Liberty and Freedom in the American Revolution.

Article Written by Rev. Scott Elliott

Sources

Unger, Harlow Giles. Lion of Liberty: Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation (p. 53). Da Capo Books. Kindle Edition.

Kukla, Jon (2017). Patrick Henry: Champion of Liberty. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-9081-4.

Unger, Harlow Giles. Lion of Liberty: Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation (p. 169). Da Capo Books. Kindle Edition.

Unger, Harlow Giles. Lion of Liberty: Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation (p. 247). Da Capo Books. Kindle Edition.

https://books.apple.com/us/book/patrick-henry/id1171100187